Executive Summary

Threat actor attribution has traditionally been considered more art than science, often relying heavily on a few threat researchers to confirm observed activity. This approach is unsustainable and contributes to confusion in naming threat groups. We have addressed this by creating the Unit 42 Attribution Framework, while leveraging the excellent work of the Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis.

The Unit 42 Attribution Framework provides a systematic approach for analyzing threat data. This framework facilitates the attribution of observed activities to formally named threat actors, temporary threat groups or activity clusters. A core component is the integration of the Admiralty System, where we assign default scores for reliability and credibility to each evidentiary object. This methodology, which allows for researcher discretion in adjusting scores, is fundamental to the tracking of threats and elevates the efficacy of intelligence collection and analysis.

- Reliability: Assesses the trustworthiness of the source, including its capacity to provide accurate information

- Credibility: Determines whether the information can be corroborated by other sources

We apply this framework across a broad spectrum of threat data, including:

- Tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs)

- Tooling, commands and configurations of tool sets

- Malware code analysis and reverse engineering

- Operational security (OPSEC) consistency

- Timeline analysis

- Network infrastructure

- Victimology and targeting

As we gather and analyze this threat data, we initially track it as activity clusters. We track these clusters over time. If we identify overlaps, we combine them as appropriate. We elevate clusters to temporary threat groups as we gain more insights. We declare a named threat group (using our constellation naming schema) only when sufficient visibility is achieved. This systematic progression prevents premature naming and ensures a consistent model for assigning group names.

Levels of Attribution

Threat intelligence is essential for stakeholders to make informed security decisions, offering both tactical and strategic insights. Attribution provides value at multiple levels. Even without definitively identifying the specific actor or country of origin, various degrees of attribution can still yield valuable results. The Unit 42 Attribution Framework outlines three distinct levels:

- Activity clusters

- Temporary threat groups

- Named threat actors

Figure 1 illustrates these levels of attribution in a timeline from activity clusters to a named threat actor.

Level 1: Activity Clusters

Attribution begins by assigning observed activity to a cluster, either by creating a new cluster or by linking the activity to a pre-existing one. During the investigation of threat activity or an intrusion, threat analysts gather various types of information, including:

- Infrastructure (e.g., IP addresses, domains, URLs)

- Capabilities (e.g., malware, tools, TTPs)

- Victims and targeting (e.g., organizations, industries, regions, temporal overlaps)

A single isolated event is usually not sufficient to form an activity cluster. While we sometimes allow singular observations to be activity clusters, in most cases we require at least two or preferably more, related events or observables. “Related” could mean:

- Shared indicators of compromise (IoCs)

- Similar TTPs

- Targeting the same organization or industry

- Occurring within a short time frame

Then we perform the following steps:

- Clearly articulate the rationale for grouping these events into a cluster

- Explain the shared characteristics and why we believe they are linked beyond coincidence

This justification is crucial for transparency and allows others to understand our reasoning.

For example, we might observe the following events:

- Event 1: A phishing email targeting a financial institution containing a malicious attachment with a file that has a specific SHA256 hash

- Event 2: A different financial institution reporting a malware infection with the same SHA256 hash

- Event 3: Open-source intelligence (OSINT) from a blog post linking this SHA256 hash to a suspected phishing campaign

These events would be sufficient to create an activity cluster. This example contains multiple related events (i.e., phishing and malware infection) with overlapping IoCs (i.e., SHA256 hash) and potential victim overlap (i.e., financial institutions). The OSINT provides additional context.

We name activity clusters based on their assessed motivation using the prefix CL- followed by a motivation tag and a unique number. Motivation tags are:

- UNK: Unknown motivation

- STA: State-sponsored motivation

- CRI: Crime-motivated

- MIX: A mix of STA and CRI

An example of a suspected state-sponsored activity cluster name would be CL-STA-0001.

What’s not needed for an activity cluster:

- High-confidence attribution: We don’t need to know who is behind the activity to create a cluster. Activity clusters are for grouping related activities, even if the actor is unknown.

- Complete attack lifecycle mapping: We don’t need to understand the full attack lifecycle at the cluster stage. We can form activity clusters based on partial information.

| Note: In threat intelligence, activity cluster and campaign are related terms used to describe adversary activity. These terms signify different levels of organization and understanding.

An activity cluster refers to a collection of observed behaviors, IoCs and TTPs that appear connected. At this initial stage of analysis, the full context of a coordinated effort is lacking, meaning there’s no clear understanding of the overarching objective or the complete attack lifecycle. Attribution may be low or uncertain. A campaign represents a higher level of organization and understanding. It involves a series of coordinated activities, often attributed to a specific threat actor or group, undertaken with a defined objective (e.g., espionage, financial gain, disruption). A campaign implies a deliberate and planned effort with a clear goal. This typically spans a specific time frame and encompasses multiple phases such as reconnaissance, intrusion and exploitation. Consider a jigsaw puzzle analogy:

|

Level 2: Temporary Threat Group

Temporary threat groups represent the second level of attribution. This concept allows us to elevate activity clusters to a more established category when we are confident a single actor is involved in the threat activity. This is true even when we lack sufficient information to attribute the activity to a named threat actor.

Establishing temporary threat groups enables more focused tracking and analysis of a threat actor’s operations while we develop the intelligence picture further.

Before we can migrate an activity cluster to a temporary threat group, it is essential to conduct rigorous checks of the collected intelligence data to ensure the grouping accurately reflects a single, distinct threat actor. An essential component of creating a temporary threat group is the mapping of identified threat activity according to the formal method of intrusion analysis known as the Diamond Model [PDF].

A thorough investigation will enable a more nuanced understanding of the activity from one or more clusters, moving beyond superficial similarities. This deeper analysis is crucial for confidently migrating an activity cluster to a temporary threat group and establishing the foundation for potential future attribution to a named threat actor. Meticulous documentation of findings and rationale is essential for transparency and reproducibility.

To minimize the chance of attributing unrelated, opportunistic events to the same threat actor, we observe the activity for at least six months. This duration ideally provides enough direct observations through case work to demonstrate persistent behavior and confirm the observed activity belongs to the same group.

We name temporary threat groups based on their assessed motivation using the prefix TGR- followed by a motivation tag and a unique number. Motivation tags are as follows:

- UNK: Unknown motivation

- STA: State-sponsored motivation

- CRI: Crime-motivated

- MIX: A mix of STA and CRI

For example, a suspected state-sponsored temporary threat group name looks like TGR-STA-0001.

Level 3: Named Threat Actor/Country

When an intrusion occurs, we often want to identify the perpetrators. However, attribution requires careful consideration to mitigate inherent biases.

Publicly associating an attack with a specific threat actor or country of origin can have significant repercussions. For example, destructive threat actors might launch retaliatory attacks. If an association is incorrect, this could lead to intelligence consumers misprioritizing security controls.

Any public mention of an association between activity and a named threat actor must include appropriate estimative language to convey our confidence levels regarding the connection. This prevents misattribution within the community and misspent resources from our stakeholders.

Promoting a temporary threat group to a named threat actor (i.e., giving a Unit 42 Constellation name) is a significant step that requires a high confidence assessment and compelling evidence. This requires strong evidence from multiple reliable sources, including internal telemetry, trusted partners and corroborated OSINT. We map the activity to all four vertices of the Diamond Model (adversary, infrastructure, capability, victim) with multiple tracked items for each of the vertices.

Determining Motivation: Cybercrime Vs. Nation-state Vs. Mixed

As part of the attribution process, we must consider:

- The threat actor’s motivations — where possible — based on their activities (e.g., stealing sensitive data, destruction of systems, demanding ransom)

- Victimology

- Possible overlaps with known activity

Determining this motivation provides the label within the activity cluster or temporary threat group name, moving from the initial unknown (UNK) state to either cybercrime (CRI) or nation-state (STA), or MIX for a combination of the two. The CRI, STA and MIX labels apply to activity clusters and temporary threat groups, as we must know the motivation of a group prior to graduating to a named threat actor.

Minimum Standards for Levels of Attribution

We leverage a set of minimum standards for each level of attribution to ensure analytical rigor, credibility and accuracy of our intelligence reporting.

Below, we outline some of the considerations that we have established to manage the promotion of activity through our Attribution Framework. We group these by type of analysis, and then describe how the considerations play out at each level of attribution.

TTP Analysis

- Activity clusters

- Groupings of similar TTPs: This includes using the same malware family, exploitation techniques or command-and-control (C2) infrastructure.

- Temporary threat groups

- Detailed TTPs: We move beyond general MITRE ATT&CK® tactics and techniques classifications and focus on the associated procedural level details and artifacts — the particular tools, commands and configurations employed.

- Custom infrastructure tools: Custom tools or scripts used for managing or interacting with the group’s infrastructure (e.g., a proprietary tool for managing infrastructure or a botnet).

- Unique infrastructure configurations: Unusual or unique configurations of common infrastructure components (e.g., a specific, non-standard setup of a web server used for C2 communication).

- TTP evolution timeline analysis: We examine the chronological development of TTP usage within the cluster. A continuous, evolving TTP pattern over time often suggests a single actor refining their methods. In contrast, sudden or major changes could indicate different actors or campaigns.

- Named threat actors

- Distinct and well-defined TTPs: The named threat actor should exhibit a set of distinct and well-defined TTPs that differentiate them from other known actors. This could include unique malware, custom tools, specific exploit techniques or a characteristic attack lifecycle. The more unique and consistent the TTPs, the stronger the case for a distinct actor.

Infrastructure and Tooling Analysis

- Activity clusters

- Overlapping IoCs: Shared IP addresses, domain names, file hashes or other indicators.

- Temporary threat groups

- Beyond IP addresses and domains: We focus on the relationships between infrastructure elements, such as shared hosting providers or registration patterns. We use these infrastructure pivots to uncover additional related activity.

- Whois and (p)DNS records: We analyze Whois and (p)DNS records for suspicious domains. We look for patterns in registrant information and nameservers, as well as other details that might link seemingly disparate infrastructure.

- Code similarities: If malware is involved, we go beyond hash comparisons. We analyze the code for similarities in structure, functionality and unique characteristics. We look for code reuse, shared libraries or other telltale signs of a common developer or codebase.

- Tool configuration: We examine the configuration of any tools used by the actor. Unique configurations, custom modules or specific settings can be strong indicators of a single actor.

- Named threat actors

- Infrastructure analysis: We conduct a thorough infrastructure analysis, linking the group’s activity to specific infrastructure elements (IP addresses, domains or servers). We demonstrate consistent use of this infrastructure over time and, ideally, link it exclusively to the group’s operations.

- Malware analysis: If malware is involved, we perform in-depth analysis to identify unique code characteristics, shared codebases or links to other known malware families used by the group.

Targeting and Victimology

- Activity clusters

- Common victims: Targeting organizations in the same industry or geographic region, or with similar profiles.

- Temporary threat groups

- A deeper dive into victim profiles: We identify specific organizational characteristics, technologies used or types of data targeted that connect the victims. We look for patterns that extend beyond general classifications. For example: Is there a common vulnerability a threat actor is exploiting that could indicate the targeting is opportunistic, based on the victims’ attack surface?

- Targeting motives: We investigate the underlying motives for the targeting. Does the choice of victims align with a particular objective, such as espionage, financial gain or disruption? Understanding the reason behind the targeting offers critical insights into the actor’s identity and aims.

- Named threat actors

- Motivation and targeting patterns: We develop a clear understanding of the threat actor’s motivation and targeting patterns. What are their objectives (such as espionage, financial gain or disruption)? Who are their typical targets (industries, geographies, organizations)? A well-defined understanding of the threat actor’s motives and targets strengthens the attribution and provides valuable context.

Temporal Analysis

- Activity clusters

- Temporal proximity: Events occurring within a relatively short time frame.

- Temporary threat groups

- Geopolitical or industry events: We correlate the activity timeline with external events, such as geopolitical developments or industry-specific conferences. Does the activity coincide with any events that might provide context or suggest a motive?

- Named threat actors

- Sustained operations: We observe consistent and sustained activity from the threat actor for an extended period of time across multiple campaigns. This demonstrates a long-term commitment to the operations and reduces the likelihood of misattributing short-lived, opportunistic activity or false-flag operations.

Other Considerations for Attribution

OPSEC tracking: We analyze a threat actor’s OPSEC practices. Do they make consistent mistakes or exhibit unique patterns in their attempts to remain anonymous? These OPSEC fingerprints can be valuable for attribution. Notable mistakes include:

- Typos in code and commands

- Leaving a developer’s handle in code or file metadata

- Open infrastructure

Absence of contradictory evidence: We take care in the presence of contradictory evidence that could disprove the single threat actor hypothesis. For instance, drastic changes in an activity cluster’s TTPs or targeting might suggest multiple threat actors or a shift in operations. Such instances warrant further investigation before promoting an activity cluster to a temporary threat group.

Exceptionally high data volume: Promotion could be warranted if a significant volume of high-quality threat data becomes available earlier than our typical timelines. This could happen, for instance, after a major incident where extensive forensic analysis or threat intelligence gathering uncovers a wealth of information about a previously unknown actor. This accelerated timeline is justified when the data provides a comprehensive understanding of the actor’s TTPs, infrastructure and motivations. The activity cluster should exhibit activity across multiple vertices of the Diamond Model.

Data scarcity: If data remains scarce after an extended observation period, promotion to a temporary threat group could be premature. Continued monitoring and data collection are crucial in such scenarios. We exercise discretion to determine an appropriate time frame for further observation, weighing factors such as:

- The nature of the threat

- Potential impact

- Available intelligence sources

The objective is to collect sufficient data for confident attribution to a single actor before formally designating it as a temporary threat group.

Evaluating Quality, Validity and Confidence

Throughout the entire intelligence lifecycle, we regularly reevaluate the quality, validity and confidence levels of our threat intelligence. Before creating an activity cluster, promoting to a temporary threat group or formally naming a threat actor, we reassess our research and perform several checks to ensure the activity cluster is valid, meaningful and based on reliable information.

- Source verification

- Reliability of sources: We assess the reliability of information sources. We prioritize trusted sources like internal telemetry, vetted partners and reputable security researchers. We are cautious with information from untrusted sources or those with a history of inaccurate reporting. We pivot from secondary sources (e.g., a news article) to original technical reporting whenever possible. We then apply source reliability ratings (A-F) and credibility ratings (1-6).

- Corroboration: We seek corroboration from multiple independent and outside sources whenever possible. If information comes from only a single source, especially a less reliable one, we treat it with skepticism and look for additional evidence.

- Indicator validity

- Context of IoCs: We evaluate the context in which IoCs were observed. IoCs without context (e.g., a file hash without knowing any additional information) have limited value. We must understand how the IoCs were obtained and what they represent.

- Uniqueness of IoCs: We assess the uniqueness of IoCs. Common tools, publicly available exploits or generic infrastructure are weak indicators. We prioritize unique or rare IoCs, especially those linked to specific threat actors or malware families.

- Volatility of IoCs: We consider the volatility of IoCs. IP addresses and domain names can change quickly, making them less reliable for long-term tracking. Malware hashes and TTPs are generally more persistent.

- TTP consistency

- Established Patterns: We compare observed TTPs with established patterns of known threat actors. Do the TTPs align with any known groups? Are there any significant deviations that raise doubts?

- Internal Consistency: We check for internal consistency within the observed TTPs. Do the tactics and techniques make sense together? Are there any contradictions or inconsistencies that suggest the activity might not be related?

- Victim analysis

- Targeting Patterns: We analyze victim targeting patterns. Do the victims share any common characteristics (industry, geography, organization size)? Do the targeting patterns align with the suspected actor’s known motives or objectives?

- False Flags: We consider the possibility of false flags. Does the victim selection seem deliberately designed to mislead analysts to implicate another actor?

- Estimating confidence assessments

- Confidence assessments: We boil these considerations down to a single, clear confidence assessment.

- Estimative language: We follow the estimative language standard set by the U.S. intelligence community.

Source Verification With the Admiralty System

The Admiralty System provides the possible values for source reliability and information credibility, as well as keywords and descriptions of the values that can be leveraged when writing intelligence reports. Table 1 contains the ratings, keywords and descriptions used in our implementation of the Admiralty System for source reliability.

| Source Reliability | ||

| Rating | Keywords | Description |

| A | Reliable | No doubt about the source’s authenticity, trustworthiness or competency. History of complete reliability. |

| B | Usually reliable | Minor doubts. History of mostly valid information. |

| C | Fairly reliable | Doubts. Provided valid information in the past. |

| D | Not usually reliable | Significant doubts. Provided valid information in the past. |

| E | Unreliable | Lacks authenticity, trustworthiness and competency. History of invalid information. |

| F | Reliability unknown | Insufficient information to evaluate reliability. Might not be reliable. |

Table 1. Admiralty Scale for determining the reliability of a source of information.

Internally, we define default scores for routine sources. For example, we set telemetry data to a default reliability score of “A.” We can adjust the score lower in cases where we find evidence of possible interference with logging or other defensive bypasses that could have impacted telemetry.

Information credibility can range between 1-6 and is assessed separately from the source’s reliability.

Table 2 contains the ratings, keywords and descriptions used in our implementation of the Admiralty Scale for information credibility.

| Information Credibility | ||

| Rating | Keywords | Description |

| 1 | Confirmed | Confirmed by other independent sources. Logical in itself. Consistent with other information on the subject. |

| 2 | Probably true | Not confirmed. Logical in itself. Consistent with other information on the subject. |

| 3 | Possibly true | Not confirmed. Reasonably logical in itself. Agrees with some other information on the subject. |

| 4 | Doubtfully True | Not confirmed. Possible but not logical. No other information on the subject. |

| 5 | Improbable | Not confirmed. Not logical in itself. Contradicted by other information on the subject. |

| 6 | Difficult to say | No basis exists for evaluating the validity of the information. |

Table 2. Admiralty Scale for determining the credibility of information.

Internaly, we established default credibility scores for a wide range of intelligence artifacts, such as:

- The standard IoC types (e.g., file hashes, domains, IP addresses, email addresses)

- Key artifacts that threat researchers use to track groups (e.g., registration information, TLS certificate details)

Again, these are default scores, and our analysts can lower or raise the score for each artifact based on their findings. For example, an IP address defaults to a credibility rating of 4 (Doubtfully True) because IP addresses can host many unrelated services and quickly change their association to specific sites and services. However, threat researchers can raise a score based on specific evidence, including situations where the IP address is hard-coded in a malware configuration with active C2 telemetry, in an active incident response case.

Both the reliability and credibility level of sources have a direct influence on our attribution process. For example, a source of information with classification of “A2” will have a much stronger influence in attribution confidence than a source with reliability “C3.”

Applying the Attribution Framework

Our long-term tracking of Stately Taurus activity provides a glimpse into the evolution of an activity cluster to a named threat group. In 2015, we published a threat research article discussing our discovery of the Bookworm Trojan along with a second article, Attack Campaign on the Government of Thailand Delivers Bookworm Trojan.

At that time, we did not have the Attribution Framework, so the articles do not mention activity clusters. However, we show that evolution in our 2023 Stately Taurus article where we assigned an activity cluster to the 2015 activity and linked it to Stately Taurus. Then in 2025, leveraging our Attribution Framework, we completed the link between Stately Taurus and Bookworm malware.

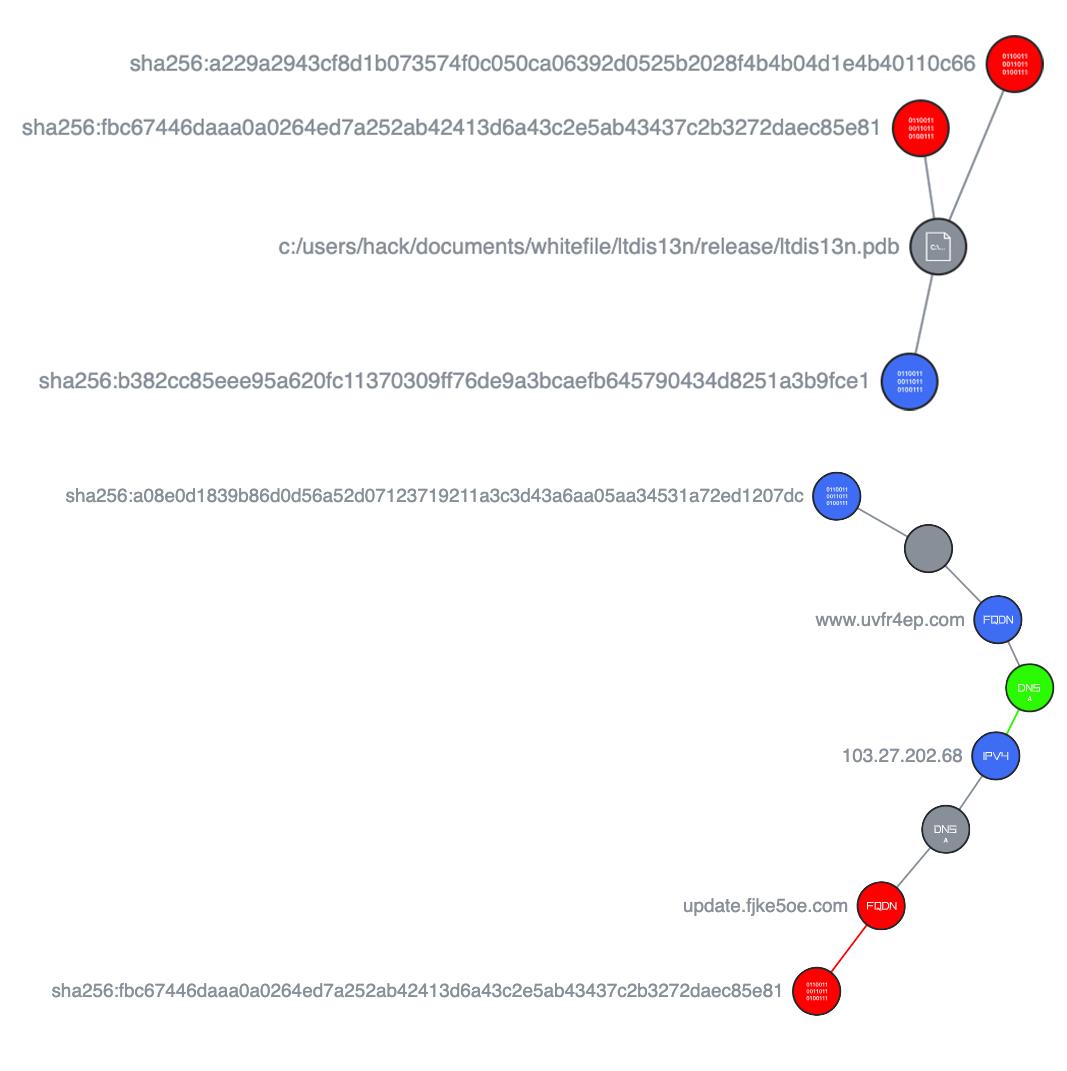

While analyzing Stately Taurus, we noted overlaps between parts of the threat actor’s infrastructure and systems used by a variant of Bookworm malware. Figure 2 maps SHA256 hashes associated with the Bookworm malware variant to the infrastructure used by Stately Taurus.

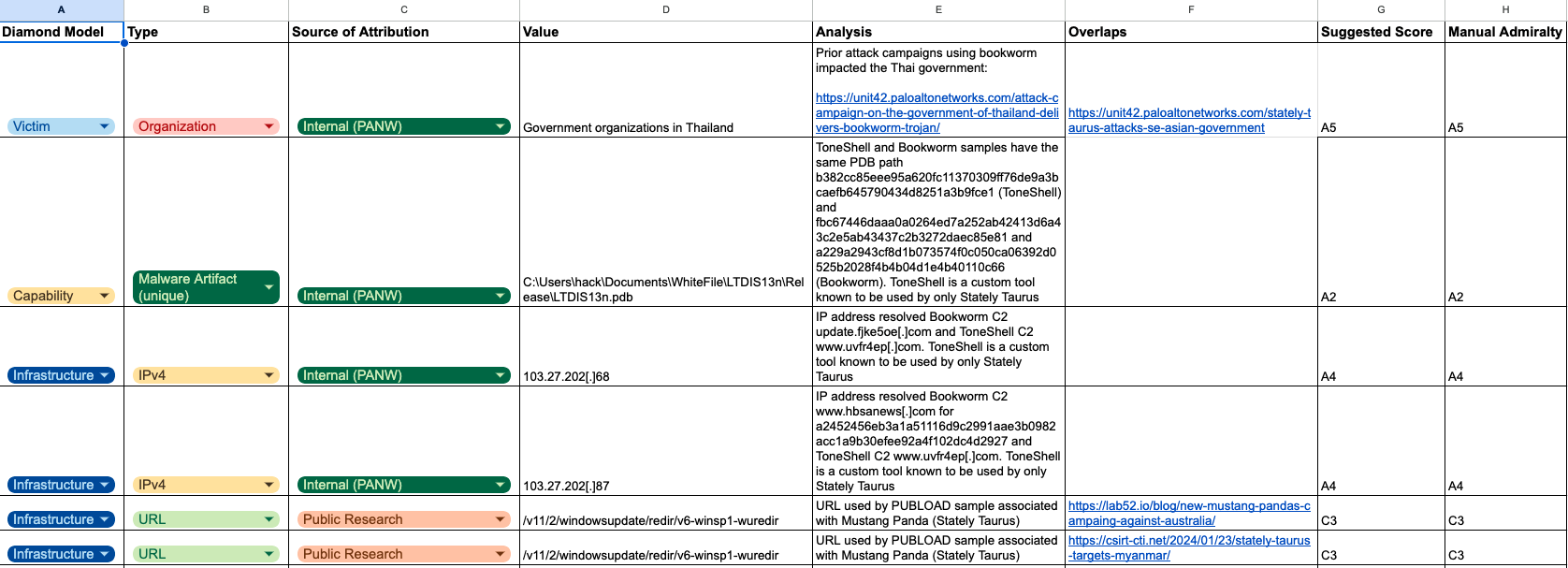

We added all the tracked IoCs, TTPs and other intelligence artifacts into our internal Attribution Framework scoresheet shown in Figure 3. We also provided details in the analysis column, including justifications to any changes of the default suggested score.

We implemented a small Attribution Framework Review Board to review findings. This board leverages members of multiple internal research teams to discuss the findings to ensure they are accurate. The review board also ensures that we have not overlooked any opportunities to build out the intelligence picture further before promoting an activity cluster to a temporary threat group or a temporary threat group to a named threat actor.

Conclusion

The Unit 42 Attribution Framework offers a structured approach to analyzing threat data. This methodology enables the attribution of observed activity to named threat actors, activity clusters or temporary threat groups with different levels of confidence. It is essential for long-term tracking and improves the efficiency of threat intelligence gathering and analysis.

We hope this framework offers our intelligence consumers sufficient transparency into our internal practices. Additionally, we hope it serves as a model for other threat research teams, contributing to the continued maturation of the threat intelligence profession.

For more information on the Unit 42 formal threat groups, check out our article Threat Actor Groups Tracked by Unit 42.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America: Toll Free: +1 (866) 486-4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- UK: +44.20.3743.3660

- Europe and Middle East: +31.20.299.3130

- Asia: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

- Australia: +61.2.4062.7950

- India: 00080005045107